On blackness, cinema and the moving image: A Kings College London symposium

Bex Shorunke

13 Nov 2016

In light of their Black Star season, BFI collaborated with Kings College London’s Department of Film Studies to curate a symposium that was both rigorously inquisitive and deeply empowering. Amidst the severe absence of black faces both in front of and behind the camera, as well as in the BAFTA’s and OSCAR’s, two conclusions can be ascertained. The first, being that Hollywood alongside other independent circles fail to give sufficient recognition to black stars. The second indicating that those black people who do manage to assume positions of semi cinematic power, are restricted in narrating their own stories by a story repertoire dominated by whites.

KCL’s symposium vowed to explore this. The discussion was led by a diverse academic panel including Rizvanna Bradley, Michael Boyce Gillespie, Hannah Hamad, Jacqueline Najuma Stewart and cinematographer Arthur Jafa. In a seamless arc, it served to trace the historical evolution of the black movie star, examine blackness in visual culture and its aesthetics, and delve into the politics of black stardom, including methods of black resistance.

Firstly however, what do we mean when we say black film? If Soul Plane is a quintessentially black film, is there then a scale upon which the perceived blackness of a film is measured? Moreover, does a black film refer exclusively to black producers, actors and content or is there room for manoeuvre? Such provocative questions were put forth by Michael Gillespie. One cultural touch point for Gillespie was Wendall B. Harris, Jr.’s noteworthy performance as the notorious William Douglas Street, Jr. in Chameleon Street in 1975. So remarkable was the picture, that in 1990 it earned the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance Film Festival.

The multiplicity of black cinema is reflective of the diversity within the black diaspora; it is something to be celebrated, not denounced.

Yet, Gillespie highlights Chameleon Street’s greatest paradox. Harris, the imaginative imposter at the films core, was praised for his cinematic capability. However, Harris as the director was slated as an imposter for producing a film that was not deemed ‘black’ enough. Post its award, Chameleon Street was subject to continual degradation by film critics for being derivative, and not Spike Lee enough. But Gillespie asks, why? The multiplicity of black cinema is reflective of the diversity within the black diaspora; it is something to be celebrated, not denounced. We should understand black cinema as a marriage between the art of cinema (therefore allowing for experimentalism) and as something that explores the discursivity of race.

Jacqueline Stewart outlined the more prominent early African American film stars in conjunction with the style black cinema took. Melodrama provided a means to which American mass culture could confront racial issues, hence why much emerging 1930s African American cinema assumed a comic form. Through this visage of comedy, moral clarity could be attained when dealing with harsh societal ills, like black and white inequality. Moreover, melodrama simultaneously functioned as a means through which black moviegoers could gain a sense of justice.

Spencer Williams, a 1940s pioneering black star mobilised these forms of humour perfectly. At the apex of his career in 1941, William produced the folklore visionary document of southern black life, The Blood of Jesus. The film bubbled over with religious resonance, wittiness and feelings of empowerment, with an eye to validate its black audience. Stewart then questions, how is it then that Williams, an autonomous ground breaking artist, backslides into clowning around in a minstrel fashion for the pleasure of white audiences in Amos and Andy? A brutal question, but one that is applicable to many black stars, and Stewart did well to explore this.

In discussing the cultural and aesthetical politics surrounding the black star, one common theme touched upon was the role of the ‘dark star’, i.e. the black star that was largely unacknowledged.

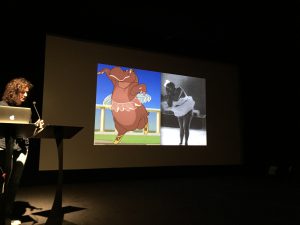

In discussing the cultural and aesthetical politics surrounding the black star, one common theme touched upon was the role of the ‘dark star’, i.e. the black star that was largely unacknowledged. Hannah Hamad speaks of the dark star in relation to anthropomorphism, a common feature of CGI animation. She states anthropomorphism is used to both evoke and gloss over the longer history of black stars. For example, in Warner Bros 2006 film Happy Feet, African American tap dancing actor Savion Glover is the dark star. Despite providing the motion capture and dance choreography for the tap dancing sequences of Mumble (the protagonist) he remains invisible to audiences, his name is omitted from the opening credits, and he is yet to appear in any of its trailers.

Hamad assures us however that Savion Glover’s case is far from an anomaly. DreamWorks’ 2005 box office hit Madagascar uses rotoscoped footage of 1940’s African American Hollywood dancer Hattie Knowle as the basis for the characterisation of Gloria, the dancing hippo. Once again recognition fails to be given, and Knowle is left in the shadows. At no point in the film is she mentioned.

Arthur Jafa registers darks stars as black individuals whom possess an iconic talent or photogenic capacity, but otherwise fall too short of white normative standards to ever be in front of the camera. At this point he quotes various dark stars, and undoubtedly the most scandalous of all was American rapper Miscellaneous. Grill encrusted teeth, a loose afro framing an emotive face that contorts and smiles to the sounds of Eddie Hazel’s guitar solo in Maggot Brain. This is what constitutes the seven-minute clip Jafa shows us, and it is strangely captivating.

Miscellaneous is a pimp by day and an artist by night. Yet over and beyond this we are still transfixed by him. Jaffa encourages us to challenge the status quo and revel in what may be considered as abject art. African American art isn’t rose tinted, it is raw. These dark stars will continue producing cinematic works that are both expressive and saturated with varying degrees of abjection. Jaffa insists it is high time we look beyond this and appreciate dark stars for all their nuances. Moreover insisting that on an even wider scale we make sure to shine a spotlight on black stars as a whole, whether or not Hollywood chooses to.