‘We are not seen as human’: black women’s experiences of living with HIV

Serena Barker-Singh

05 Jun 2018

Florence was six months pregnant when she found out that she had HIV. She was at the hospital for a routine scan when a midwife asked her if she had ever been tested for the virus. Knowing that it would be in the baby’s best interests to find out her HIV status, she agreed to the test, which showed that she was HIV positive. Florence was advised to tell two other people – the father of her child and an old ex that she thought could be at risk of also having HIV. She made the call to her former partner. He was angry when he heard the news; he attacked her, and threatened to buy a gun with the sole intention of shooting her if the results came back positive. He called her the following week telling her that the test results had come back negative.

Violence against women is a widespread problem: in the UK, two women are killed each week by a partner or former partner. Jess Phillips MP reminds us in the Commons each year on International Women’s Day the scale of the problem by reading out the number of women who have died at the hands of domestic violence, and each speech remains just as powerful as the previous. A study released earlier this month by Britain’s oldest HIV charity, the Terrence Higgins Trust, has exposed how prevalent violence is in the most vulnerable of places: within the HIV community. The study estimated that over half of women living with HIV in the UK have experienced violence.

“Many women of colour living with HIV, like Florence, feel invisible”

Recent figures released by Public Health England stated that the largest group of new HIV diagnoses are black women of African descent (46.1%). In spite of this, many women of colour living with HIV, like Florence, feel invisible. When Florence received her test results, she engaged with a network of support groups, which she credits as her initial lifeline of support. However, she also reflects that these groups were limited by the fact that they largely catered to specific issues faced by men. She yearned to meet more women living with HIV, and found some women were already organically forming their own groups to fill the vacuum. The Terrence Higgins Trust’s report revealed that since the start of the epidemic in the 1980’s, UK media and policy focus has been exclusively on men living with HIV/AIDS. This narrow approach acts as a significant barrier to effectively understanding and meeting women’s needs.

Many young women living with HIV have concerns that are simply not being addressed. Mercy, who was born with HIV, explained to me that she is part of the first generation in the UK to know how to manage their medication since birth – but she is worried about the toll it might take on her body. There has been no research into what she calls the “femininity of HIV” and she is keen to find out the effects of taking daily medication, especially on her fertility. Research into living with HIV hasn’t yet focused on issues that disproportionately affect women in a meaningful way. Research into pregnancy and HIV have particularly focused on the child and parent-to-child transmission rates rather than the person carrying the child themselves. The report also found a lack of understanding of the diversity of the sexualities of women living with HIV, and pointed out that women who are not heterosexual or who do not fall into an “at risk” group are simply not understood by health services.

“45% of women with HIV live below the poverty line, and 58% of women living with HIV experience violence”

By ignoring the specific needs of women – who roughly make up 1/3 of all those living with HIV in the UK – it’s not surprising that people like Mercy are suspicious about why they have been overlooked by researchers and clinicians. As Mercy explains: “in general [HIV] affects marginalised communities and that’s part of the reason people don’t listen. It’s a problem on the margins.” Mercy comments that as a woman with HIV, she feels people perceive her as having a status that is “less than human”. It is her way of explaining the horrifying statistics which reveal that 45% of women with HIV live below the poverty line, and that 58% women living with HIV experience violence: she says “they don’t see us as human.”

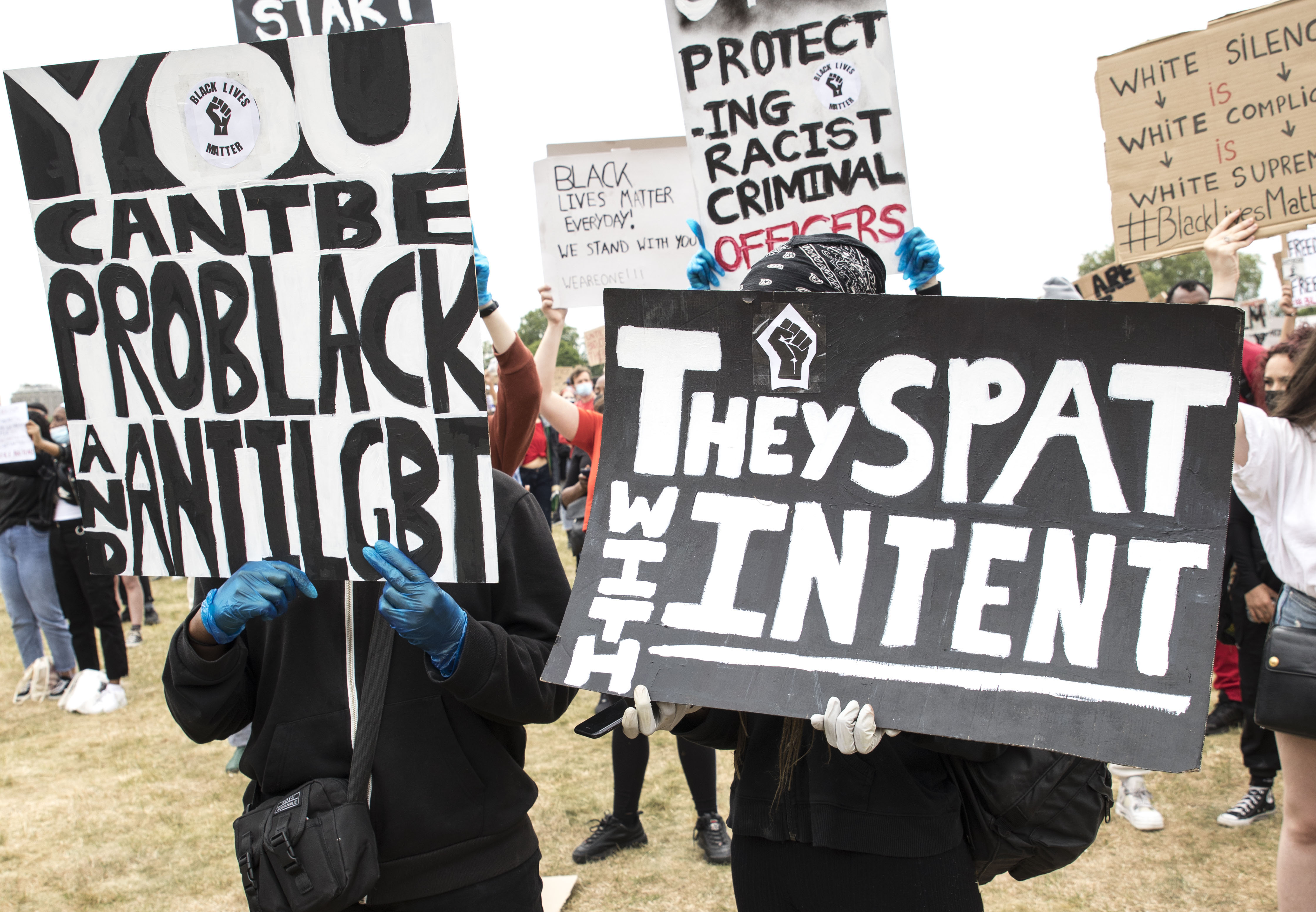

The call for a more diverse support network isn’t just symbolic. The National Aids Trust (NAT) reports that: “Black African men and women living with HIV experience stigma and discrimination not just related to their HIV positive status, but also to their status as migrants and as black African. HIV prejudice, racism and xenophobia combine and interact to exert significant burdens and pressures”.

“In 2015 Nigel Farage called for people who have tested positive for HIV to be banned from migrating to Britain”

Florence explains how her Nigerian family have pulled away since she first spoke to them about her diagnosis. The father of her child stayed in contact to find out that her son had not contracted the virus, but changed his number soon after the news and cut off all contact from then on. Mercy explained how even some family members urged her not to talk to her siblings about her HIV, even though she was diagnosed at birth. Of course, stigma is not confined to BME communities – many of the women I spoke to point out a single verbal attack on them that has lingered since 2015 when Nigel Farage called for people who have tested positive for HIV to be banned from migrating to Britain. Mercy sees Farage’s quote as a reiteration of her point: that people like her are not seen as human – that somehow the virus has stripped their humanity from them. But she reminds us also that the H in HIV stands for that very thing.