The October Gallery’s recent exhibition of Ghanaian photographer James Barnor’s work is a striking reminder of the ability photographs have to tell stories about people that are rarely discussed in national curriculums and media.

Barnor’s work features exquisite classic imagery of Ghanaian and black-British women from the 1950s onwards. The subjects look like any other female of the post war era, with big bouffant hairstyles and colourful shift dresses. The works capture the subjects in Accra, Ghana’s capital, and in London where Barnor shot some of his iconic work during the 1950s and 60s. In his Accra works, the photographer captures the city at its most optimistic point: emerging out of the staid era of British colonialism, looking forward to a freer, self-determined future. The subjects could have been in any metropolitan city- only the tell-tale surroundings give away the location.

Therein lies the power of photographing black people all over the world. Barnor’s photos put the black-British connection on record much earlier than their representation in mainstream British media.

Drives by various corporations and industries to hire more black and minority ethnic staff can make it seem as if black people only became relevant and productive in recent times. Barnor’s work has the effect of placing black people as participants in bygone eras, which they are excluded from in national and collective memories.

Another essential shift these photographs make is to broaden the historical identity of who the ‘African woman’ was in times past. Of course there is no typical African woman, just as there is no typical European woman. However, the photographs refute the archetypal European representation of the African woman, as helpless, poor, mute and generally the opposite of beauty. The photographs capture a carefree frivolity, which presents the optimism and activism of the 60s as an international phenomenon, not just something that happened in the UK, Europe and America.

For the young black psyche, there is something soothing about seeing yourself represented in the history of the place you call home. A recent advertorial which appeared on BuzzFeed featured photos of London Street Style through the years, starting from the 1920s. I clicked on it out of curiosity, and was shocked to scroll through the pictures and find photos of black Londoners dating from the late 1940s. One particularly striking photo, captured two black girls in matching outfits in Wembley in 1986, a pleasant surprise for this North London native. As a British school pupil, I was taught to assume that British history had nothing to do with me as a black person, that my grandparents’ arrival to the UK was too recent to make it onto the record. The record which was taught in school anyway.

Visual histories act as resounding affirmations. When Beyoncé samples Yoruba body artistry for a visual love letter to accompany her latest album, it centres black stories of the past in the present and creates a link between the two. It links black stories on the African continent with the stories of a much wider diaspora. It presents black representation as a communal experience and not limited to an individual’s personal identity.

Visual histories are effective, because they represent people like few other mediums can. They are a format that cannot be argued with. Photographs of black people relaxing at home, in 80s hair styles and shoulder pad jackets, as in the Black in the Day photo project, offer a talking point for black and non-black people alike. They invite society to see black history as intertwined and simultaneous with their own, rather than something that happens removed from the society they live in.

Barnor is credited with getting black women’s magazine covers sold alongside popular international women’s titles. It is essential to know that the presence of black people in media, although still limited, is not just a fact of life. Pioneers like Barnor made possible editorials that served as reference points for what would come after him- Naomi Campbell in the UK springs to mind. Jourdan Dunn, a British model, who works for brands internationally is a contemporary example. There has to have been a first back then, for there to be an example right now. Undoubtedly that ‘first’ is Barnor.

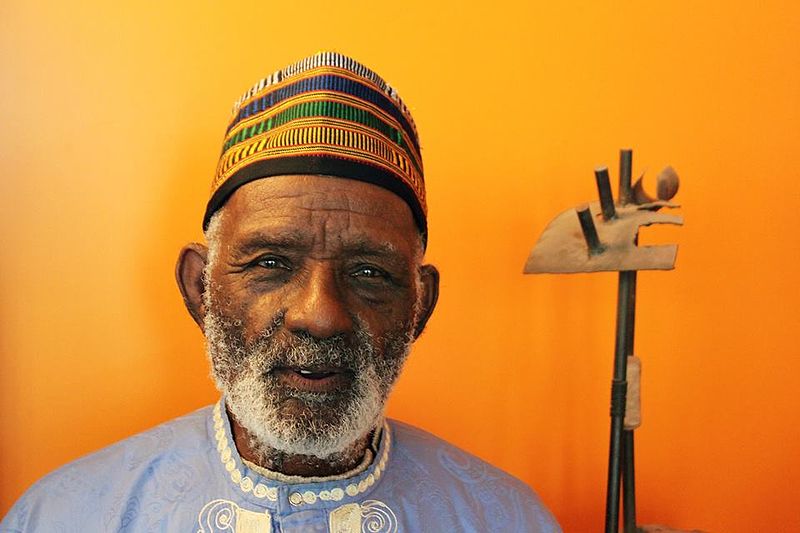

Barnor himself credits photography for the impact it has on representing people in the past:

“What stands out about photography for me is the rememberability, or the fact that it brings back memories. The fact that we can depend on photography now to make history, or record history, that’s what I like more than anything.”

Photographs, especially colour, are powerful visual histories of who black people have been in their places of origin and in Britain too. To have a history is to know where you belong, and to not feel disorientated by the present discomfort black people endure as minorities in the UK, Europe and America. It is to know that, with our history on record in Britain, at home, we cannot possibly be foreigners.