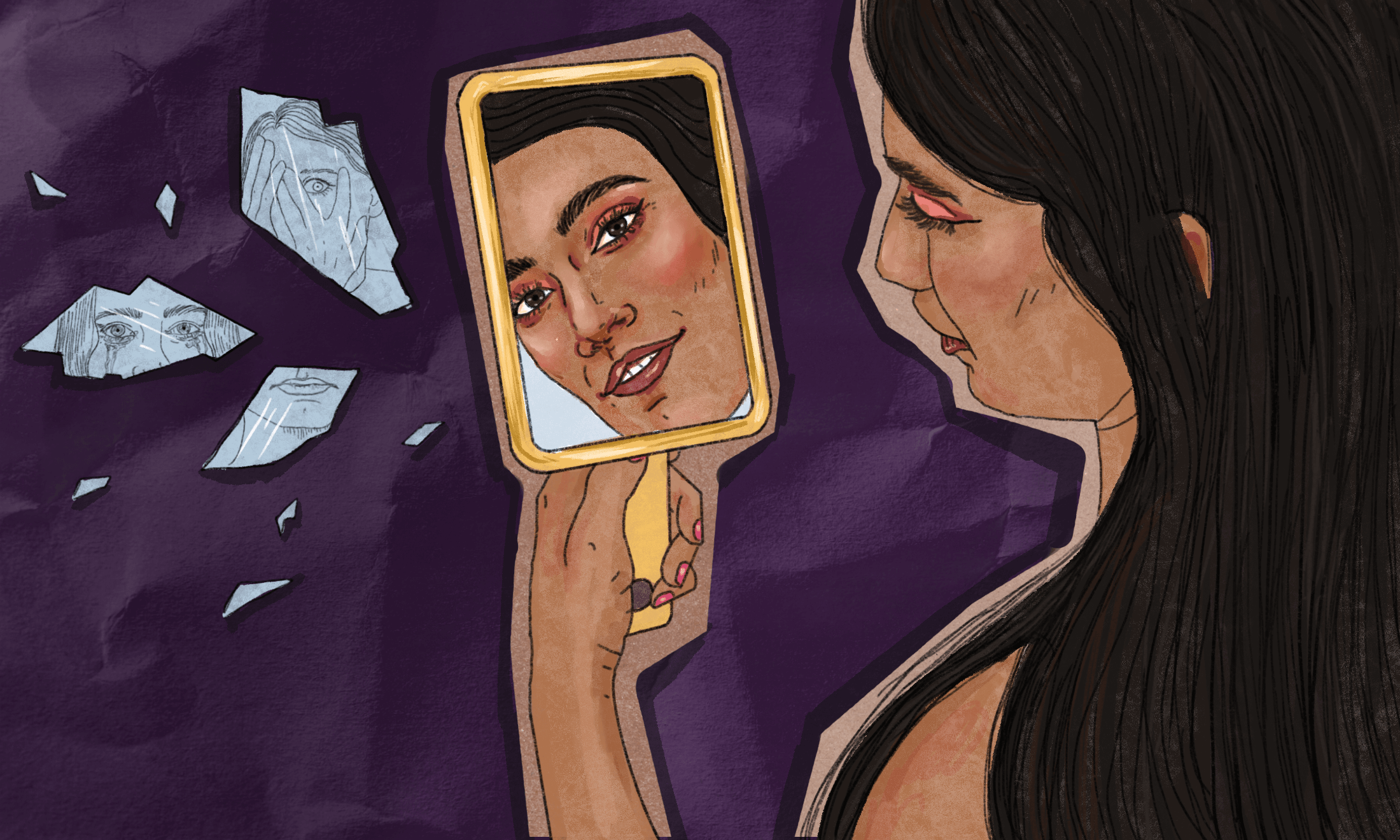

I have struggled with self-harm from the age of 16. Over the years, I’ve slowly become comfortable sharing my experience with self-harm in hopes that I’m doing my part for mental health awareness, but sometimes being so open and honest about my mental health isn’t always liberating. I often find myself in uncomfortable situations, having to defend my complicated and very much misunderstood addiction to self-destructive behaviour.

Becoming a mental health advocate doesn’t come with a step-by-step guidebook on how to manage difficult conversations, and as “open” as I am with sharing my experiences, I never really feel prepared to answer questions regarding my self-harm scars.

I started to notice pretty early that the conversations I was more reluctant to have were a result of the inquirer being from similar ethnicities to my own. After weeks of uncomfortable staring, an ex-colleague asked about my self-harm scars, and I answered honestly. She then explained – after her initial shock – that she had seen “stuff like this” before, but would have never expected it from someone like me because “us black people don’t do that.” It was with bitter realisation that I admitted to myself these conversations were going to be much harder than I thought.

“By choosing to believe mental illness doesn’t happen in our communities many people are not getting the care they require”

Dumbstruck, and for once, speechless, my passion for educating mental health through my experiences had faded, leaving me feeling inadequate. Overwhelmingly, I answered her following questions the best I could.

What I wish I had explained is that mental health problems can be experienced by everyone regardless of race, culture or religion, and that idealisations like her own are a big part of why many people of colour are ashamed to open up and seek the help they require. It’s fear of judgement. The Mental Health Foundation states that black and minority ethnic groups are in fact more likely to be diagnosed with a mental health condition, more likely to be admitted to hospital and experience a poor outcome from treatment, and more likely to disengage from mainstream mental health services.

It also says: “African-Caribbean people are also more likely to enter the mental health services via the courts or the police, rather than from primary care, which is the main route to treatment for most people. They are also more likely to be treated under a section of the Mental Health Act, are more likely to receive medication, rather than be offered talking treatments such as psychotherapy, and are over-represented in high and medium secure units and prisons.”

So, to respond to the statement, yes, unfortunately us black people do do that.

As a society, we have come so far with mental health care. But we still have a long way to go, as many still refuse to open their eyes and minds to something that is massively affecting everyone around us.

By choosing to believe mental illness doesn’t happen in our communities many people are not getting the care they require due to social stigma and shame. Vital conversations that need to be had are being avoided resulting in stereotypes and discrimination, and people like me feeling somewhat embarrassed to share their stories, even if it is to bring awareness.

“Mental health is certainly not exclusive to white people and stigma and discrimination only result in social exclusion”

Undoubtedly, self-harm is a sensitive subject and something not everyone is open to understanding, so having these conversations and addressing common misconceptions to bring awareness to an illness that holds much stigma and discrimination is really important to me. Shifting narratives is something I’m trying to portray within my writing but I often feel like it isn’t enough. The more we have the conversations the more open we become to discussing mental health. We break down barriers for our friends, our neighbours, our brothers and sisters so they don’t suffer in silence and can get the help and support they deserve.

The 2014 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey found that 93% of people from black and minority ethnic (BME) communities who have mental health problems face double the levels of discrimination with the most common areas of mental health discrimination for BME communities concerning making and keeping friends (68%), being shunned by people that know they have a mental health problem (68%), finding a job (68%), keeping a job (67%) and in social life (67%) – mental health problems are becoming life-limiting for some people. Previous research found that people using secondary services experienced the highest levels of stigma from being shunned, amongst family, friends, in their social life and with mental health staff.

Discussing mental health with the older generation can and will be difficult, but if I was brave enough to educate my blissfully ignorant colleague about my battle with self-harm, I can only hope, that from our short and very awkward conversation that day, she can take away that mental health is certainly not exclusive to white people and that stigma and discrimination only result in social exclusion. As a community, we have suffered in silence for way too long and it’s time we started having important conversations that encourage us to change our own stigma. I hope that sharing my story will help others, not only in the depth of their addiction, but being brave enough to share and educate on the reality of mental health in our communities.