At the process with which our mouths adjust to the intricacy of language, we become acquainted with the importance of truth. In accepting this reality, we are forced to familiarise ourselves with clichés that lay commonplace on our tongue until we no longer remember their original meanings.

“Honesty is the best policy.”

“The truth shall set you free.”

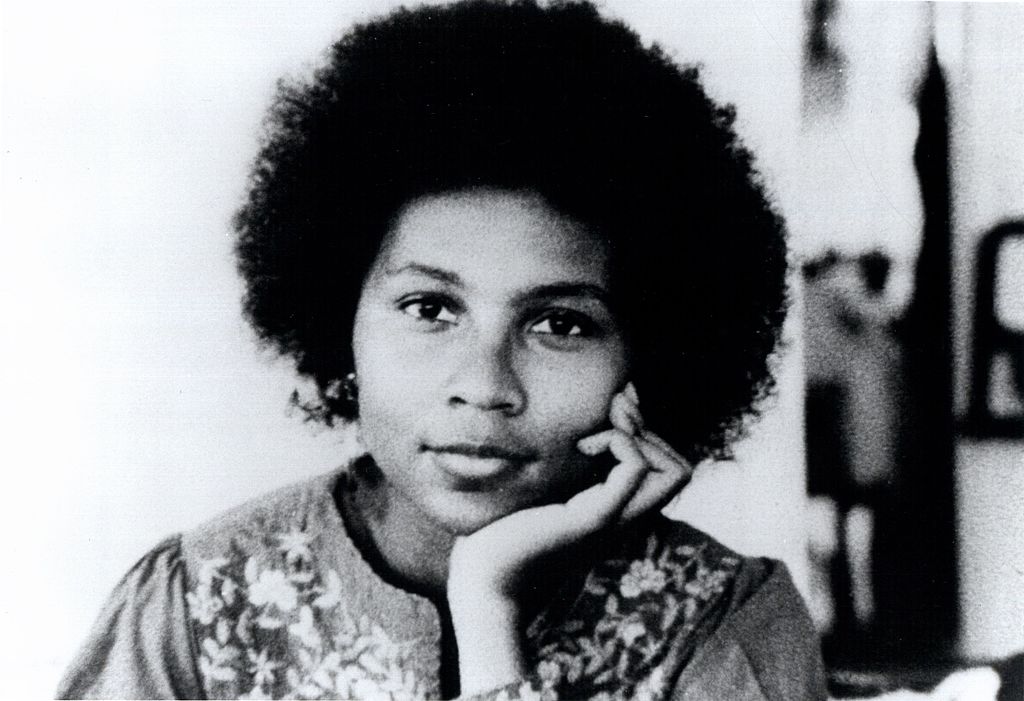

It is a testament to the power of simplicity that such aphorisms will go on to take a sombre significance as we grow up. My reminder came as I discovered Sisters of the Yam by bell hooks, a literary manifestation of the sisterhood and self-recovery that hooks advocated among black women. It is based on the premise that effective movements for social change that emerge among women necessitate the self-actualisation of the individuals within it. Thus weaved throughout the book is a call for healing, one that would begin on the individual level, and go on to display itself in the aims of a collective.

To heal insinuates that there is something to be fixed, that there exists an imbalance somewhere within the subject. In reality, however, I did not arrive at Sisters of the Yam seeking recovery or believing that I needed mending. I approached the book for a myriad of reasons. The central and most unoriginal being that having been deprived from black and female intellectuals by a curriculum that sought to give me a “full education”, it was necessary that I pursue my own.

Perhaps implicitly, as so often happens with one’s journey towards self-recovery, I sought guidance. My revelation however, came with the first chapter, titled: “Seeking After Truth”. In this chapter, hook maintains that speaking the truth in our lives is the point at which healing takes place within us. The illuminating nature of such an assertion forced me into a confrontation with myself that demanded a re-evaluation of what truth means for me. It was thus inevitable that I’d discover that seeking truth, and really being dedicated to its cause requires a mutilation not only of ones self but also of the reality that one, perhaps unknowingly, has carefully constructed.

At six years old, after growing up in Ghana, I arrived in London with several expectations. These expectations would go on to lay uninvited at the front door of the one bedroom flat that I would share with my mother, father and sister. It was a home that would hold its breath in shame when forced to house the disillusionment of the aunts/cousins/relatives passing through to confirm whether the streets of London were really paved with the metaphorical, yet literal, gold we were all willing to invest in.

Years later, my dad will laugh as he reminds me that on my first day of school I asked him what English I would speak there. I wish he had told me that at six years old I should not already be choosing between truth and conformity. Perhaps, in the broken language I trusted him to fix, he would have foretold nights spent re-inventing dinners to wash out the sounds of banku and fufu. Perhaps he would have predicated the eventuality that I would no longer be able to speak to my Grandma, and that it would be in exchange for exclamations over how good my English is. Or the myriad of times I would be forced to navigate my blackness, my African-ness, in spaces too small and too unwilling to accommodate it. Perhaps it would not have made that much of a difference.

Even so, it has always bothered me that, even at such an age, I could have an intuition about the way in which the world works. That in being dishonest, I could intimate but not wholly recognize that the world itself is not so. That my skin colour and my heritage do not exist in a neutral world. When my reality and those of others are therefore trivialised because they do not accurately represent the dangerous notion of a racist and prejudice free world there exists a problem. It is for this reason that hooks maintains that resistance can only be conducted if we are first able to recognise the concealed truth of institutionalised and commonplace domination/discrimination. In this way, “we can only recognise reality by breaking through denial.”

Dedicating oneself to truth is a militant act. Projected inwards, it is a journey towards self-love that at first brutal and rough, finds its end in a gentleness and patience with ones’ self. Projected outwards, it displays an assuredness that goes on to reject and violently react against anyone or anything that seeks to repress one’s truth, one’s reality, and one’s struggle. My truth, even in the partial one I’ve chosen to share, scares me firstly for the shame and guilt that shrouds it. However, speaking it is a testament to my first step towards liberation. One that according to hooks must first begin with the self and go on to be demanded for all.