TW: mention of suicide and self harm

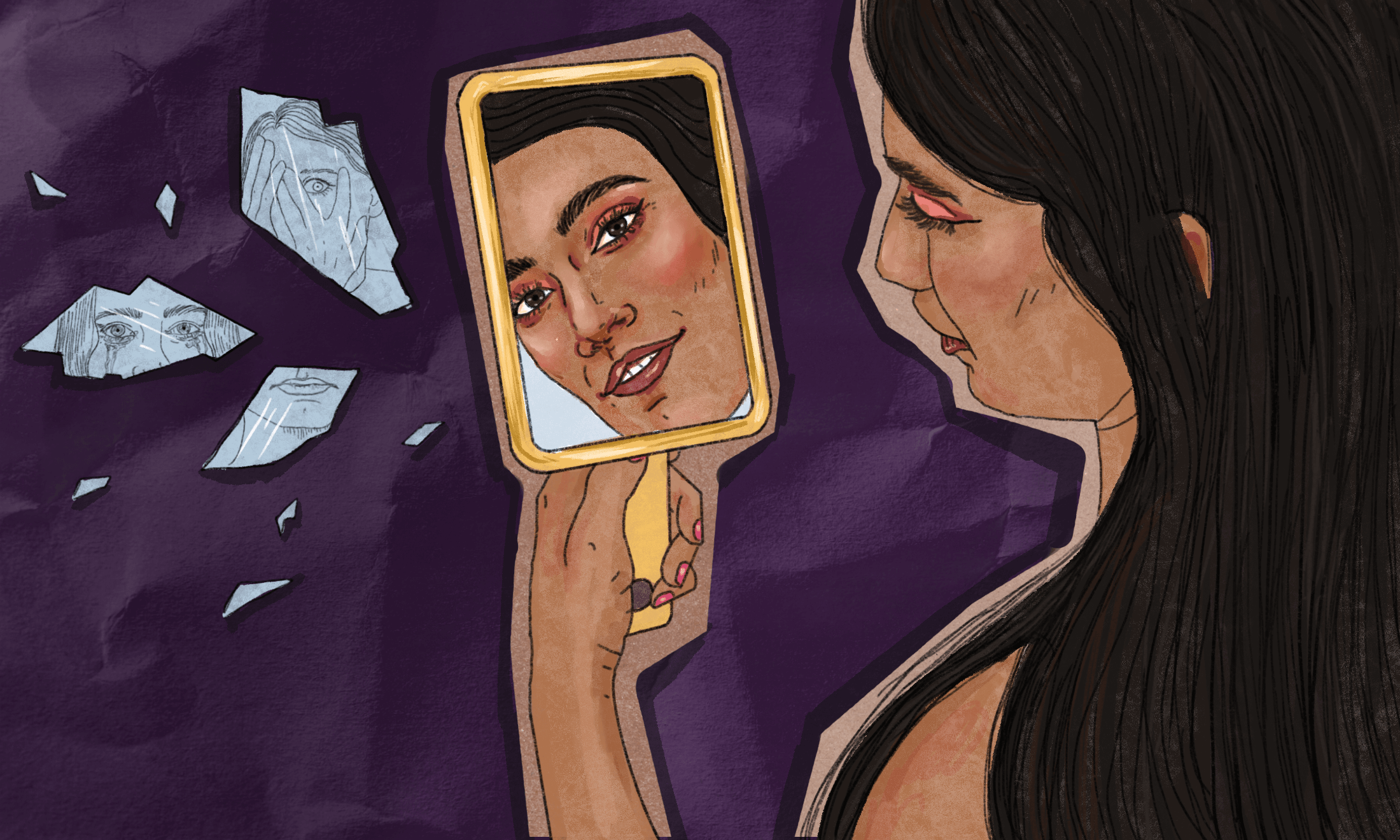

Living with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) is sometimes compared to living as a burn victim; you’re incredibly fragile, and you experience everyday emotions at an incredibly magnified level. Being so overwhelmed by emotions that for the most part, are not real, has made life unbearable, at times. Your vision of the world is clouded, making it difficult to function as ‘normal’.

BPD has hindered my experience as a 20-year-old who should be enjoying herself at university. But beyond this, experiencing BPD whilst grappling with my identity as a Tamil woman, has left me feeling confused and misunderstood. My parents are Sri-Lankan Tamil, and I am wholeheartedly proud of them and where I came from. But while I love the beautiful parts of my culture; the food, the traditions and the bindi’s white people love to wear at festivals, I often feel my experience with BPD could have been easier had I not been a Woman of Colour (WoC).

“He went on to explain that this was not something a normal Sri-Lankan girl would feel”

A friend noticed a major shift in my mood and energy when I was 15, (something I’d hoped would go unnoticed) and she encouraged me to go to a doctor. I was hesitant because my mum still made all my doctors’ appointments. As cruel as it sounds, I thought she’d laugh at me if I told her what it was for, so I put on a dramatic performance of a common cold. My dad drove me there and waited outside. The doctor was British-Asian, and my initial nerves around discussing the issue worsened by the minute. I told him I thought I was depressed, that I had suicidal ideation, how I felt that nothing in my life could stop me from feeling like I would be better off dead. He asked, “what country are you from?” I replied, “Sri-Lanka”.

He went on to explain that this was not something a normal Sri-Lankan girl would feel, he told me I shouldn’t be feeling low at school because Sri-Lankan people are smart and should love going to school. He laughed out loud when I told him I’d planned to pursue Drama in the future, and then he made me call my dad to come in because he thought it was bizarre that I was there without my parents. I had to sit there and listen to two men in their early fifties discuss how I was feeling and how those feelings were not valid.

“My dad talked about how he’d told me that I was dramatic before, and I never listen”

So, I sat there in tears, in disbelief. My dad talked about how he’d told me that I was dramatic before, and I never listen, and the doctor told him not to let me pursue Drama. It’s important to note this has not been my experience with every British-Asian doctor after this, but for my first experience confiding in someone about how I felt, I was put off discussing anything until I attempted suicide for about the fifth time in 3 months (after which a nurse told me I was too pretty to be sad, and I felt hopeless yet again).

I took my first overdose when I was 15. My dad’s first reaction was to scream at me and say “she’s just an actress” and “she’s doing this for attention” to my mum, who was rushing to get me to hospital. I don’t have anything against him for it, he had never faced a situation like this in his life before, because no matter the tragedy, he never reacted emotionally. He suffered violent, racist attacks when he first moved to Ireland at the age of 18. When him and my mum moved to England, they responded to racism by not reacting, by simply by getting on with their day. But I reacted to racist kids by crying, as any sensitive kid would, and I was always confused by my parents telling me not to. I’ve come to understand now that it was all just toxic pride.

“The culture tends to see mental illness as weakness, which has an impact on how I experience BPD”

Unfortunately, my parents were not prepared to deal with BPD, a disorder that makes me feel emotions so intense that I question whether I even exist. After several attempts at taking my life, I was put onto Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAHMS). Whilst the counsellors I interacted with were incredibly patient and kind, they were obviously not trained to resolve the problems that Tamil women face. The culture tends to see mental illness as weakness, which has an impact on how I experience BPD.

When CAHMS brought my parents in for family therapy, I don’t think they prepared for the shitstorm at hand. My dad refused to believe I was mentally ill. My mum (who tried SO hard to understand) couldn’t get to grips with the language they were using and how there was no logical explanation for why I felt this way. This doesn’t mean they haven’t improved since, my dad tries to comfort me when I’m sad by reaffirming that I’m a “bright girl” (although we still don’t talk about BPD). I stopped telling my mum how I felt because I worry her sick everyday that she won’t have a child the next day – but I know she’s the first person I would go to if I were to lose control again.

“they just didn’t understand that my hesitance to talk about my BPD came from years of being taught not to burden others with my problems”

University has introduced me to others who suffer with BPD, although it’s had a downside; I was talking to a friend about how I don’t feel so alone because of another girl I know with BPD, and they responded: “I don’t think yours is as bad as hers though, I’ve seen her freak out way more than you”. This felt like a knock, not that it was their fault, they just didn’t understand that my hesitance to talk about my BPD came from years of being taught not to burden others with my problems, because “Tamil people are prideful people”. Being told to “open up and talk to your friends about your episodes” by healthcare professionals, and then being told that I should figure out my problems on my own by my family, are difficult paths to navigate simultaneously. I either don’t speak about it all, and there are friends who don’t know I’ve struggled with a debilitating mental health illness for 5 years. The people who I am the closest to, know too much and have felt the burden on an extreme level, but I only know extremes and nothing in between.

No one really recovers from BPD, but recognising that my identity as a WoC has impacted factors beyond my control, feels like a step in the right direction in relieving myself of the guilt I have felt for so long.