As someone who is both British and Indian, it’s hard to walk into the British Museum and not feel the weight of my own heritage locked up there. Within the stone halls there is more of India’s history than I might otherwise ever have known; shrines, statues of gods, sculptures, thousands of years of sacred heritage. But it’s locked in a place that I cannot touch, and I cannot help but notice, as I read about Indianness, that this place that feels so English.

Last week, I was reminded of my discomfort in this space once again. The British Museum’s Keeper of Asia, Jane Portal, responded to a tweet asking about making museum labels easy to understand for all audiences. In her reply she said that the British Museum labels aim to be understandable by the average 16 year old, and “sometimes Asian names can be confusing, so we have to be careful about using too many.”

Predictably and rightfully, the Twittersphere was outraged. One commenter pointed out that “5 year olds will confidently rattle off five-syllable dinosaur names” and others noted that museums comfortably manage “name variations in the Western/Classical world”.

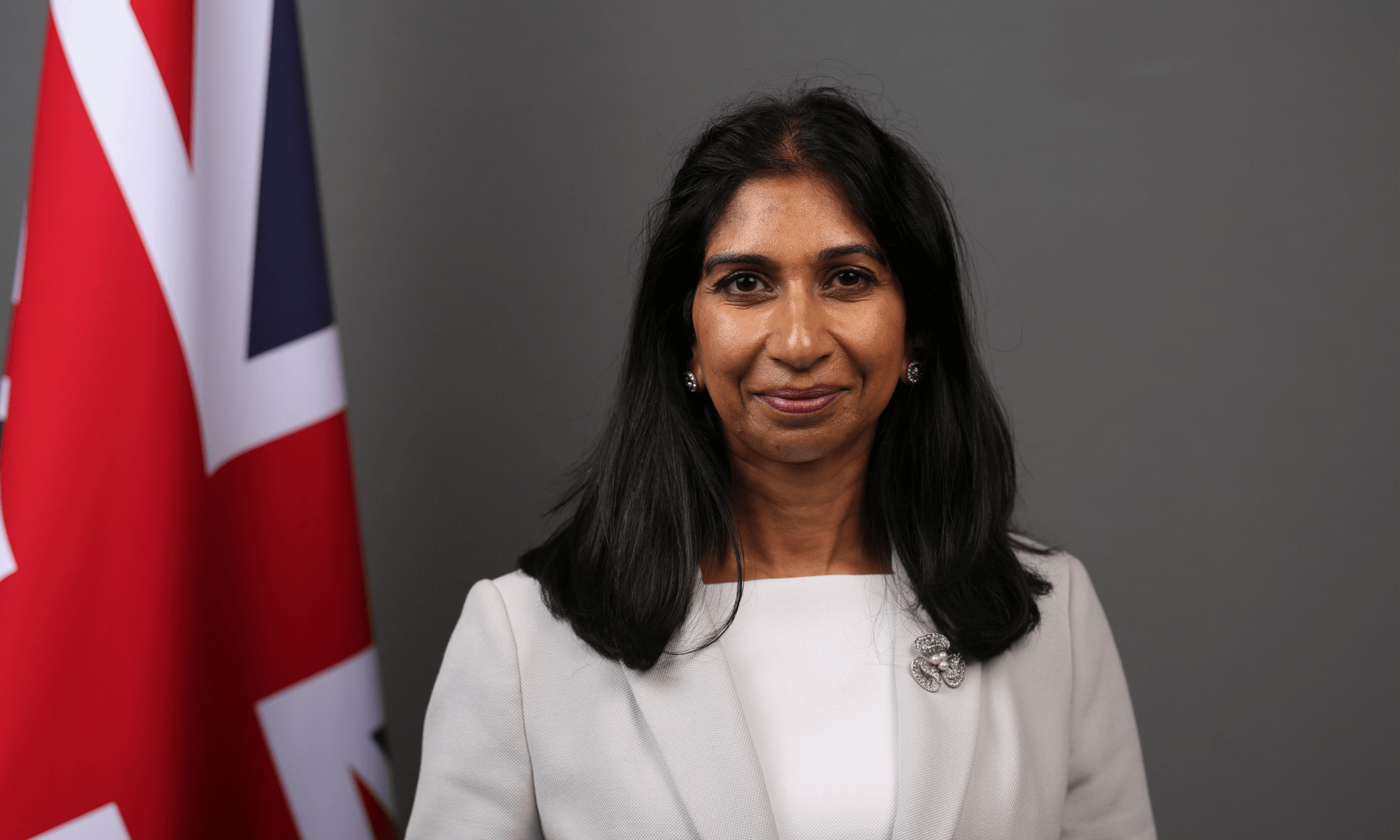

Dr Portal’s comment reminds us that the British Museum was built on the white gaze. For her, “Asian” is the unfamiliar “other”. For several hundred years the British Museum has held the spoils of white conquests and it has displayed these “foreign” objects to white British patrons. The expectation of whiteness from visitors is so deeply ingrained that the white ‘Keeper of Asia’ can tweet out a hasty few lines without considering how the statement might affect ethnic minority communities.

The feeling of being caught in between cultures in a museum is something a lot of second generation immigrants feel. For me it’s the distance between my British education and my Indian cultural identity, an uncertainty that I conceal with the convenience of the label “British Asian”. But it’s also a sense of historical distance, in knowing that the power structures that built such institutions did not build them for me.

“Dr Portal’s comment reminds us that the British Museum was built on the white gaze”

In their brief statement the British Museum failed to notice that the anger at the Twitter incident comes from a deeper sense of displacement, the overwhelming feeling that museums are places where people of colour can see their heritage on display, but where we, so often caught in an uncomfortable cultural complexity, do not feel welcome.

Perhaps this sense of displacement emerges because the British Museum is often better at telling the stories of collectors than of the blood they spilled. The founding story on their / its website mentions nothing of the bloody violence visited upon many of the communities who created and owned the artefacts. Instead there is an uncomfortable, liberal use of obscure terms like “collection” and “acquisition” to describe the actions of English imperialists who assembled the contents of the museum.

“The British Museum is often better at telling the stories of collectors than the blood they spilled”

Museum collections built upon invasive white curiosity do not simply become acceptable because the rule of the British Empire is over; they need more than time to detoxify their colonial overtones.

The British Museum continues to host incredible, fascinating exhibitions often assembled with nuance and detail. But navigating modern Britain requires a historical institution built for all the communities that live here. In short it requires radical change, opening up a deep critical engagement with colonialism, telling our stories, and exploring our experiences as non-white communities, not peripherally but within the very fabric of the institution.