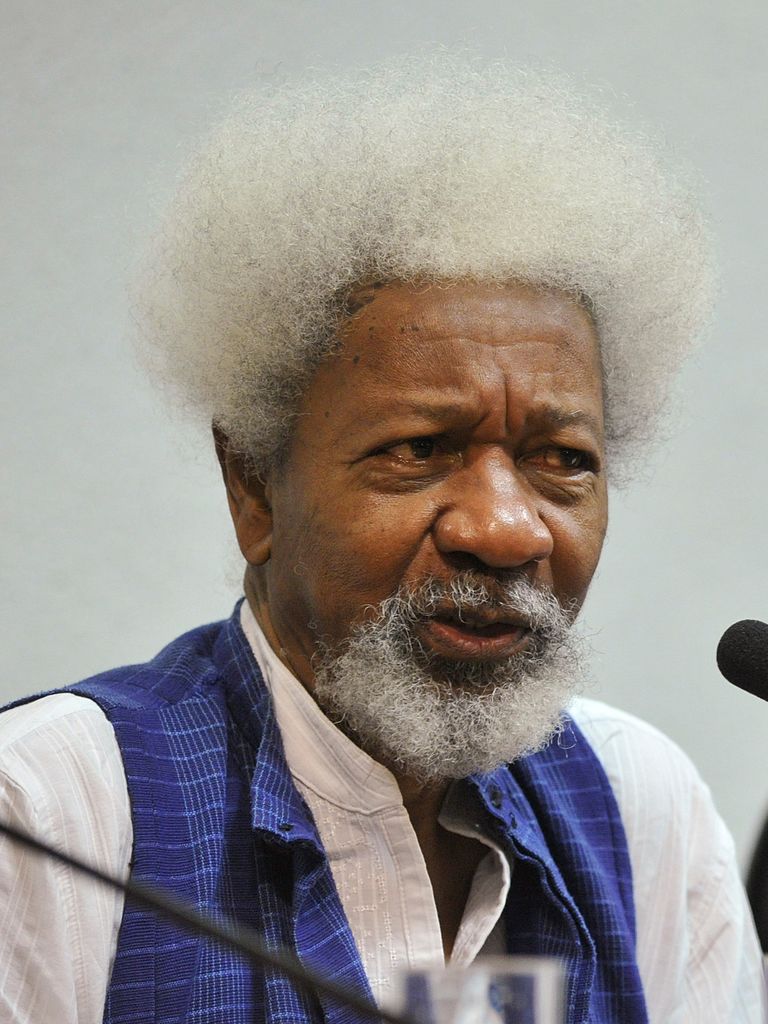

“I felt I had been sent here to be killed”, Akinwándé Oluwolé Babátúndé Soyinká, Nigerian poet and playwright said of his first winter in the United Kingdom as a student. Relaxed, confident and naturally funny, Mr Soyinka, in a sold out centenary talk at SOAS University, entertained a crowd of those who both grew up on his work, and those whose parents have encouraged a recognition of the great man.

“He taught my Dad in Ife,” my friend next to me says, beaming. Soyinka, known by most as Wole Soyinka, has an admirable ease about him. He is the writer of over 25 plays, including Death and the King’s Horsemen’ (1975), seven poetry collections, including A Shuttle in the Crypt (1971), two novels, and many more essays, films, short stories and memoirs. The list of his achievements is seemingly endless, and his passion for them is genuine.

When asked about his favourite literature, he lists Charles Dickens and the curious names of his fascinating characters, such as David Copperfield’s Uriah Heep, he notes the “emotions of literature in the rawest sense” he found in Euripides’ Medea, and, to some reserved laughter, mentions the Bible, saying, “it is one of the greatest pieces of literature in the world. They may call it revelations, but it is literature.” I thought it was hilarious. Most inspiring though, was his remark about how widely he read as a child, “I read magazine advertisements as though they were literature” he says, laughing at himself a little. Whilst the idea itself is funny, his desire to absorb any and all literature is derivative of the level of dedication he gave to his passion for literature from such a young age. It’s both inspiring and challenging, as a standard by which hard work and true desire to succeed might be measured.

Of his country, Soyinka is poetically enamoured. When asked about what makes Nigeria great, without hesitation he says, “its multiculturalism, its multinationalism, its cosmopolitanism – it’s so rich.” This love for his country is what one presumes inspired much of his political action throughout his career, and what also resulted in his exile from it, on two occasions. Reflecting on those times, he jokes about trying to convince himself that he was simply on “a political sabbatical”. Remembering his 22 months spent in prison, as a result of his trying to avert a civil war in the late 1960s, he recalls that the worst of that time was not that he was imprisoned, but that the guards made sure to keep all writing materials away from him.

Nonetheless, during his incarceration, he wrote various politically driven pieces. When asked by a member of the audience about whether or not oil’s existence in Nigeria was a curse or a blessing, he thinks for a while, then somewhat sadly says, “it’s a curse […] oil itself is not a bad thing, but what it has done is.” During this discussion he says rather solemnly, of why he continues to engage himself politically, “When you see children rooting around in the garbage for food, you want to get back to what you want to be doing, so you say, ‘let me quickly take care of this problem.’”

Among the numerous success Soyinka’s career has reaped, his Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986 is by far the most recognisable. At the mention of it he half-smiles. I’m sure in his mind he is wondering how to describe his feelings about it both honestly and without sounding ungrateful. He says the achievement itself was a good one, but the expectations that followed it were unrealistic and unfair. “The expectation to be everywhere”, as he describes it, is one that he is not fond of, as he laughs, reciting the words of his fellow winner George Bernard Shaw: “I can forgive Alfred Nobel for having invented dynamite, but only a fiend in human form could have invented the Nobel Prize.”

Visibility remains a sore-point for Soyinka, who has spent much of his life under both public and political scrutiny. On this point, Baroness Valerie Amos, host of the talk, mentions a both hilarious and rather aggressive sign posted outside Soyinka’s property deep within a forest in Nigeria which states that “trespassing vehicles will be shot and eaten”, in order to deter cars from entering onto his land, placed after he came home from a long trip to find a family picnicking outside his house. “There are times when one just doesn’t want to see a human being” he says, to much laughter. I can’t help but agree, as surely, after a life lived like Soyinka’s, a little solitude is not too much to ask.

Inevitably, as it always seems to, the question of the EU Referendum, migration and refugees soon emerges, and Soyinka, with a sigh, eloquently and intelligently addresses the topic, stating that, “If these [European] countries look into their history, they’ll see they too, took up space […] there’s movement, and that movement is not about to stop.” This brought sighs of agreement and sadness from the audience, who for maybe a brief moment, had forgotten about the international turmoil, having been enamoured by Soyinka’s stories throughout the evening.

Further delighting us, Soyinka spoke about his love for language as a “community cohering mechanism”, and the power of literature, explaining that, “literature can hone the movement towards resistance […] that’s why dictators hate it”, whilst reminding us to “keep [it] in view”. Towards the end of the evening, a young British-Nigerian woman stood up, first greeting him in Yoruba, “Ẹ ku alẹ” (“good evening”), this placing a smile on his very youthful face (he’s 82 but looks 52) as he replied, “Ṣé àlãfíà ni” (essentially, “is it that you are well too?”). She asked how, as first and/or second generation British Nigerians, was it possible for us to keep both the Yoruba culture, and the language itself, as a part of our children’s lives. He sighed and said, “well that’s a difficult question,” before thinking for a moment, a wise but serious look on his face, and saying, “make them feel like they’re missing something.” A thought that now comes to mind when I wonder how we might teach future generations about the joy that is Wole Soyinka.