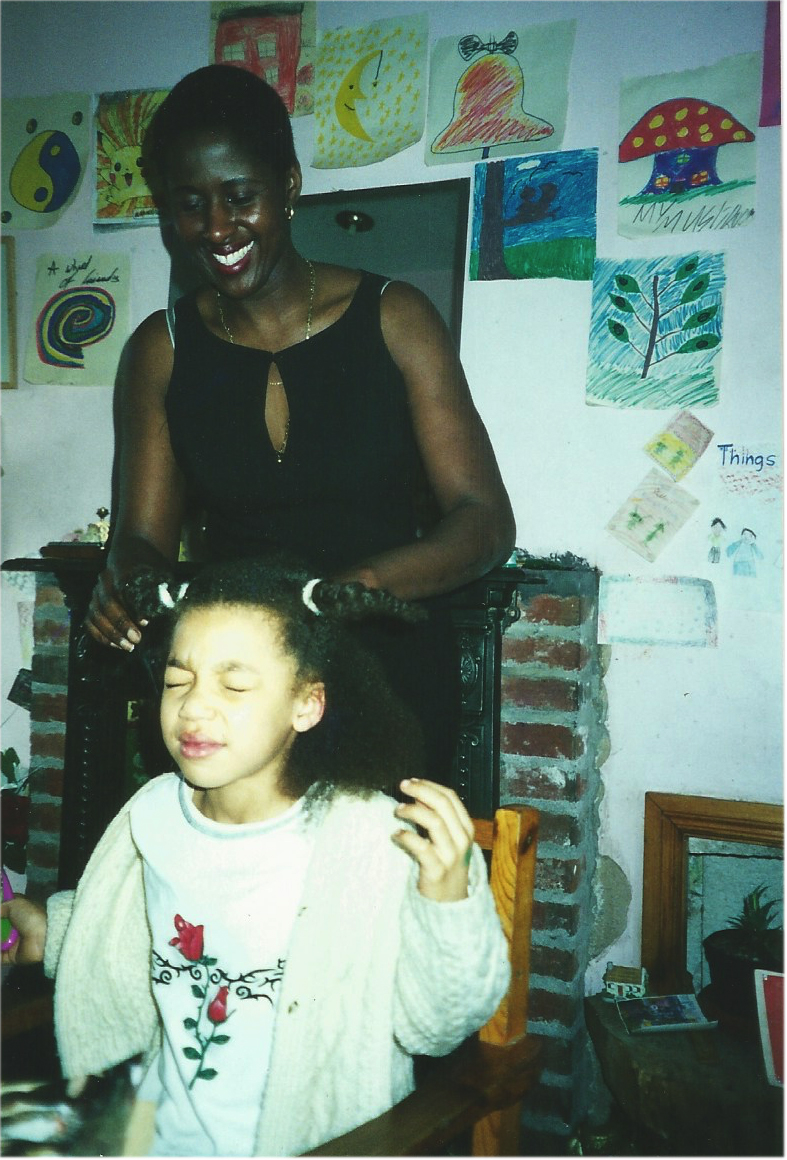

Charlie Brinkhurst-Cuff, who has been relaxing her hair since age 12, breaks down why afro hair is still such a “problem”.

In the UK in 2016, there still seems to be a general misunderstanding of afro hair and its cultural and social significance. This significance exists because it is, excepting skin-tone, perhaps the most clearly perceivable marker of African heritage; and unlike skin tone, it is something that can be quite easily manipulated. In a 2011 study by Mintel, a market research provider, it was found that up to 65 per cent of African American women do not wear their hair naturally. Although there are no comparable figures for black British women, the numbers certainly appear to be similar, and both can be traced back to the racially devastating impact of the slave trade.

The vast majority of material regarding how black people have viewed their hair historically has centred on the African American experience. As Ayana Byrd and Lori Tharps (authors of “Hair Story: Untangling the Roots of Black Hair in America.”) wrote in a recent article for the New York Times, “Enslaved and free blacks who had less kinky, more European-textured hair and lighter skin — often a result of plantation rape — received better treatment than those with more typically African features”. Although slaves are recorded as being proud of their hair, wearing it in a multitude of different hairstyles inspired by their African ancestors, as historian Shaun White points out, what followed slavery was “an era of hair-straightening in which the potential of African American hair for stylistic innovation was largely denied”.

In modern society there is no denying that a lot of the processes that black women put their hair through are in an attempt to make it appear straighter, which in turn could be equated to them conforming to the white aesthetic ideal. Since the early twentieth century black people have been using dangerous methods to alter their curls. From the ‘conk’, a corrosive lye, potato and egg mixture that was as likely to burn the scalp to shreds as it was to straighten it, to the slightly less dangerous hot comb and oil pressing method, even after emancipation natural curly hair was widely regarded as unkempt and messy. To fit into Western society, and to give themselves the best possible opportunities in life, women (and some men) were expected to straighten their hair, and it could be argued that this notion pervades in our society today. Natural hair advocate and vlogger Debbie Owsu describes how even now “If I was going for a job interview I would consider going to get a weave or a wig. I would not feel comfortable just going there with my natural hair at all.” This reasoning obviously stems from the fact that she feels people would judge her natural curls and view them as being unprofessional.

As explains Valerie Wallace Sahel, a hairdresser at well-known black hair salon Hype Coiffure, “The media has a big part to play in women wanting straight hair and weaves. You don’t see that many black role models with natural textured hair in magazines or on T.V.” And she’s right. The media portrayal of black women shows nearly all of them to be straight, or wavy haired. Think Beyoncé, Michelle Obama, Oprah Winfrey, Tyra Banks, Thandie Newton, Jordan Dunn, even Jessica Ennis. None of these women sport their hair in its natural state. It is pressed, synthetic hair sewed and glued tightly onto the roots in a “weave”, bombarded with chemicals and treatments, and wider society follows suit. When Tyra did decide to go “natural” on her T.V talk show in 2009, it was so significant that it became a news event. As noted in a recent article by the New Statesman, even the commonly used words used to describe black hair are negative; both in the media and beyond. “My hair is routinely described in pejoratives,” writes Emma Dabiri, “Frizzy. Coarse. A problem to be managed.”

But although it may have begun with slavery and been emphasised by a media dominated by white standards of beauty, it seems that this element of racism has been internalised. There is plenty of evidence of black women giving each other a hard time about their hair textures, and lauding “good hair”. Student Anna Lisa-Ghazal, who has soft ringlets rather than a curlier texture, explains how “my fellow mixed race friends always say ‘You’re so lucky, you got the ‘good’, or nice, mixed race hair!’”

In Chris Rock’s questionable 2009 ‘Good Hair’ documentary, he gave a summation of the reasons why some black women choose to chemically straighten their hair. Explaining to a white scientist he states, “Black people; black women; some men – put sodium hydroxide in their hair to straighten it out.” “Why would they do that?” asks the scientist. “To look white,” replies Chris Rock.

This explanation may seem crude, but speaking to Zimbabwean student Paida Muyambi, she candidly reveals that the reason why she straightens her hair is to look whiter.

“European, sleek, straight style hair is always portrayed as glamorous,” she says, and this sentiment of glamour is echoed by Debbie who also states that straight hair “is considered glamorous and pretty.” Despite this, there are many reasons why Rock’s overview of the reasons why black women decide to straighten their hair can be seen as simplistic.

Although it appears there is no denying that the essential reason why women started to press, weave and chemically straighten their hair is because of colonialism and racism, in some communities the current reasons behind women wearing their hair straight, or donning a weave or a wig, have transmuted into something more complex.

“I don’t think that they actually consciously want to look like they’re white,” says Debbie. “When I was wearing weaves it didn’t even cross my mind that ‘oh, this is a similar texture to white people’s hair’. I wasn’t thinking that at all. I was just thinking I don’t have very nice hair and I want to have nice hair.”

And many other women agree. “I wouldn’t say it is to look more white no, but there is something rather more Westernised about the concept of having a weave,” states Anna. Greer-Aylece, another black student who has worn her hair naturally since 2011, believes that for the majority of black women “wearing a weave or relaxing their hair is not so much about trying to look whiter as it is about feeling empowered. Feeling able to have control of their own bodies.” There is clearly a variety of reasons for black women altering their hair. Some do it because they find it easier to manage, some because their employers would be unhappy with them sporting their natural hair, and some simply because they like the way it looks.

However, although black hair care has developed since the days of the conk, there are still dangers surrounding many of the commonly used black hair regimes. This is one of the things Chris Rock delves into in his documentary, as he discovered the true nature of the chemicals used in relaxers (the common name for hair straightening creams). A worker at a factory that makes the product tells him that, “the slightest little bit of these chemicals can really cause harm to the body. A splash of sodium hydroxide in your eye can potentially lead to blindness.” Corrosive lye (sodium hydroxide) is still the main ingredient in many modern-day relaxers and causes all kinds of problems, from burnt scalps to hair loss. Additionally, other common methods such as weaves and braids can cause a receding hairline and traction alopecia due to the extensions that pull on the scalp. As afro hair trichologist Natasha Dennis, of the Black Hair Care Clinic, London, notes in a recent blog, “Traction alopecia has been the most common and frequently diagnosed hair loss at my clinic for the past few years.”

Debbie, whose hair began to fall out due to weaving, believes it is this motivating factor that is causing many women to go natural, and doesn’t think the argument that afros are difficult to handle can be used as an excuse for women not to go natural. She cut her previously relaxed hair off five months ago, and explains how now “it takes literally five minutes to do my hair. It’s the same as wearing a weave or having any other hairstyle.” She has become a part of a widespread natural hair movement connected online through the use of vlogging and blogging; collectively aiming to encourage women to wear their afros proudly, and use natural hair products that cause less damage. This movement, far more than the use of weaves, wigs and relaxers, seems to truly embrace the versatility of black hair.

In 2013 Mintel released another report which found that, due to the natural hair trend, there has actually been a 23 per cent decrease in hair relaxer sales in America since 2008. So although there is still a long way to go in black women’s acceptance of their hair, with the natural hair movement growing in America and beyond, there is still hope that this part of black culture can be reclaimed from white, Western ideals of beauty.