Sitting in the press screening of Black Panther waiting for the lights to go down, the excitement was palpable. Black and non-black journalists alike sat waiting, desperate to see this film, desperate to see if it lived up to the hype, if it could truly signal a shift in the way black narratives are depicted in cinema. As the screen flickered to life I felt a wave of nerves. This movie couldn’t be a let down – there was too much at stake.

But 20-minutes in and I could relax – it was great. Joyful, funny, exuberant – the perfect balance of tension, comedy and action with the kind of quality performances we have come to expect from Marvel movies. The narrative is nuanced; it manages to touch on feminism, racism, colonialism without oversimplifying or becoming saturated and losing the fun. Black Panther isn’t a great black superhero movie; it’s a great superhero movie, period.

But I know that black people will take more pleasure than anyone else from watching this film. I know because I felt it. To see black characters framed in this aspirational, boundlessly powerful way is rare and joyfully empowering.

Representation matters, but what matters even more is the context of that representation. There are plenty of black faces on our big screens – but the difference is that they are gangsters, slaves, drug dealers or the comic sidekick. Rather than simply saying we need more black characters, what we need is the right kind of black characters. And this is what Black Panther delivers in spades.

“They are the heroes we have been waiting for – completely unsanitized and unapologetically black”

Chadwick Boseman plays T’Challa, the returning King of Wakanda, and he is the leading man through and through. Flanked by family and allies (Letitia Wright and Daniel Kaluuya are particular standouts) and an army of female warriors, they are undeniably heroic and the universe they inhabit is utterly convincing. They are kings, heroes and fierce intellectuals – aspirational in every sense of the word, and miles from the gritty, violent, struggle-laden black lives we are used to seeing on screen.

They are the heroes we have been waiting for – completely unsanitized and unapologetically black. They speak with African accents, wear traditional outfits, rock natural hairstyles. This isn’t a blackness that has been made palatable for Western audiences; this is a blackness that is understood and recognised by black people. Danai Gurira flings her wig as a weapon during a fight scene and the audience lost it – there’s a level of playfulness and in-joking in this movie that speaks directly to the audience and their lived experiences. To see jokes like this about natural hair and African aunties in a mainstream Marvel movie is kind of ground-breaking, and hopefully signals a normalization of black narratives on screen.

What I love about this film is its staunch supernaturalism. Black heroes on screen in the past, from Blade to Shaft and Cleopatra Jones have been firmly tethered to the earth, grounded in the grubby realities of human life, battling corruption, criminals and authority. Even Blade, with its clear fantasy elements, is set on Earth, and we get little insight into the context of the vampire existence. Black Panther reacts strongly against this – propelling the story to Asgardian levels of fictionality.

“Danai Gurira flings her wig as a weapon during a fight scene and the audience lost it – there’s a level of playfulness and in-joking in this movie that speaks directly to the audience”

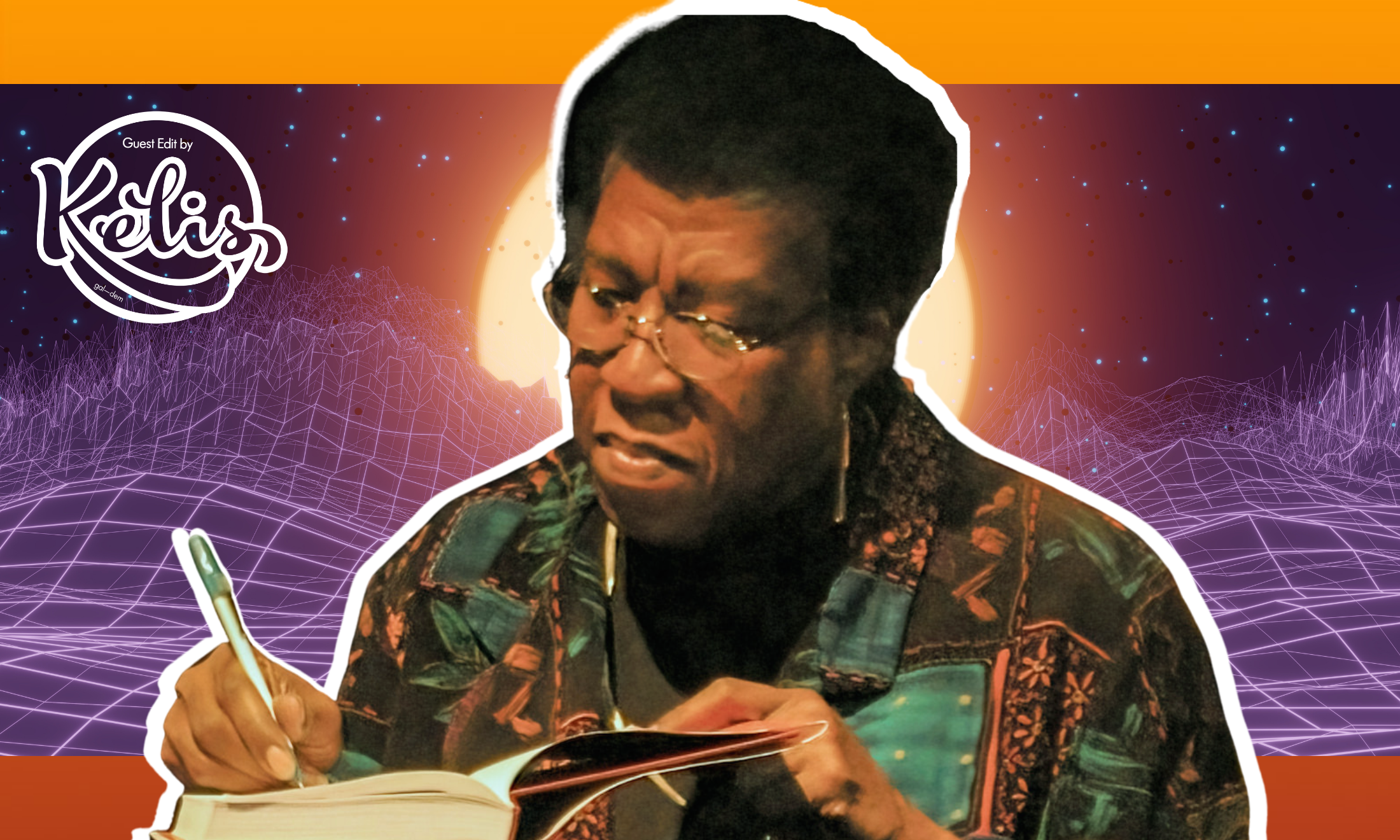

Every element, from invisible space ships to healing vibranium beads, is fantastical, and I love it. Why shouldn’t black stories have the ability to transcend the real? Science fiction is a world in which people of colour have historically been excluded. So to wholeheartedly subscribe to an otherworldly narrative is hopeful and speaks of a distant future or alternate reality that includes their stories. It is Afrofuturism at its finest.

Another world in which black people have traditionally been excluded is the horror genre. We all know the black guy dies first, which doesn’t often leave much time for meaningful narrative arcs or depth of character. Daniel Kaluyaa’s other smash hit, Get Out, completely flipped this. The instant cult classic centralizes black stories in an unfamiliar context, and the effect is stunningly powerful.

Both Black Panther and Get Out tell a black story. Whether it’s the microaggressions minefield of meeting your white partner’s family, or issues of ingrained colonialism and misrepresentation of Africa – these are stories unique to the black experience. And that is the difference; these filmmakers are not shoehorning black casts into white stories – they’re building their own from a collective cultural experience. This is why they resonate and this is why they work.

And it’s not just black people who are here for this. Record ticket sales for Black Panther and an Oscar nomination for Daniel Kaluuya in Get Out shows the appeal is wide reaching and suggests that the industry might be finally be ready to open the door. There is a deeply passionate audience desperate to hear these stories told. I hope black filmmakers keep telling them until black superheroes become part of the norm rather than the exception.

Check gal-dem’s interview with two stars of the film, Lupita Nyong’o and Danai Gurira, here.