Earlier this year, the world’s largest human trafficking trial took place in Thailand, with over 60 individuals found guilty of crimes relating to the capture and trafficking of migrants for profit. This was an extraordinarily long and very public trial, beginning with the discovery of two mass graves in 2015, and culminating in the sentencing of dozens of high-ranking Thai officials and their accomplices. Despite the obvious importance and far-reaching impact of this scandal, the case received nothing more than a cursory mention by the global news media, and it’s unlikely that the average person on the street knows of its existence.

This raises the question: what is it about the act of trafficking that prohibits the media from talking about it? Human trafficking has long been an international issue, yet it’s rarely mentioned by mainstream outlets, consistently flying under our political and educational radars. More profitable than drugs and second only to the arms trade, its $150bn annual turnover has pushed this atrocious trade in human flesh up the ladder of profitable crimes, yet it still isn’t receiving the amount of attention required to put pressure on the relevant bodies to end the practice.

A key issue is that while academic research on human trafficking is available to government policymakers, it remains frustratingly inaccessible to the public. Most research exists in costly online journals, which are only available to those who can afford subscription services. In the rare event that non-wealthy, non-academic people manage to pass through these exorbitant paywalls, they often find that the language used is dense and indecipherable, and that material referenced in these articles is again, hard to track down. This creates an endless cycle of cost and complexity that often dissuades people from doing further research.

This information chasm is not unique to human trafficking – the issue also applies to data around domestic violence and female genital mutilation (FGM) – experiences which, like trafficking, disproportionately impact women and girls. However, efforts to tackle these forms of violence in the UK have been much more coordinated and sustained than approaches to end human trafficking. The idea that domestic violence or FGM directly affects people living in the UK encourages relevant bodies to advocate for victims in a way that is not replicated in the approach to supporting victims of trafficking.

By its nature, trafficking spans countries and crosses seas and borders, meaning that datasets gathered by different agencies are hard to cross-reference and standardise

This leads to popular collective imaginings of human trafficking as a crime that happens exclusively to “other people”. Trafficking is a crime that largely affects people who migrate to the UK (often forcibly) – who are frequently Othered and politicised in the media. At all levels of society, from education through to support services, victims of trafficking find themselves with no advocates and no support, purely because of their nationality.

Part of the problem is the scale of the issue- by its nature, trafficking spans countries and crosses seas and borders, meaning that datasets gathered by different agencies are hard to cross-reference and standardise. Closer to home than Thailand, instances of human trafficking have been steadily increasing in number throughout the UK, with London seeing a staggering 60% increase in reports of trafficking and crimes relating to modern slavery.

We hear about similar cases time and time again: a 28-year-old woman who had been serving a family in Rochdale since she was just 12 years old; a 14-year-old Nigerian boy who – after being promised a better life in the UK – had his passport taken and was forced to work as a “house boy” in West London; an underfed and overworked Filipino maid, whose employer held her hostage and refused to pay her. Another piece of the puzzle is that trafficking is likely a much under-reported crime, due to the nature of the abuse which is premised upon exploiting power and fear. People with less power and resources because of their age, gender, or socioeconomic status are typically targeted by traffickers: children and women of colour are disproportionately affected by trafficking, as well as people who don’t have family or other support networks they can turn to for help.

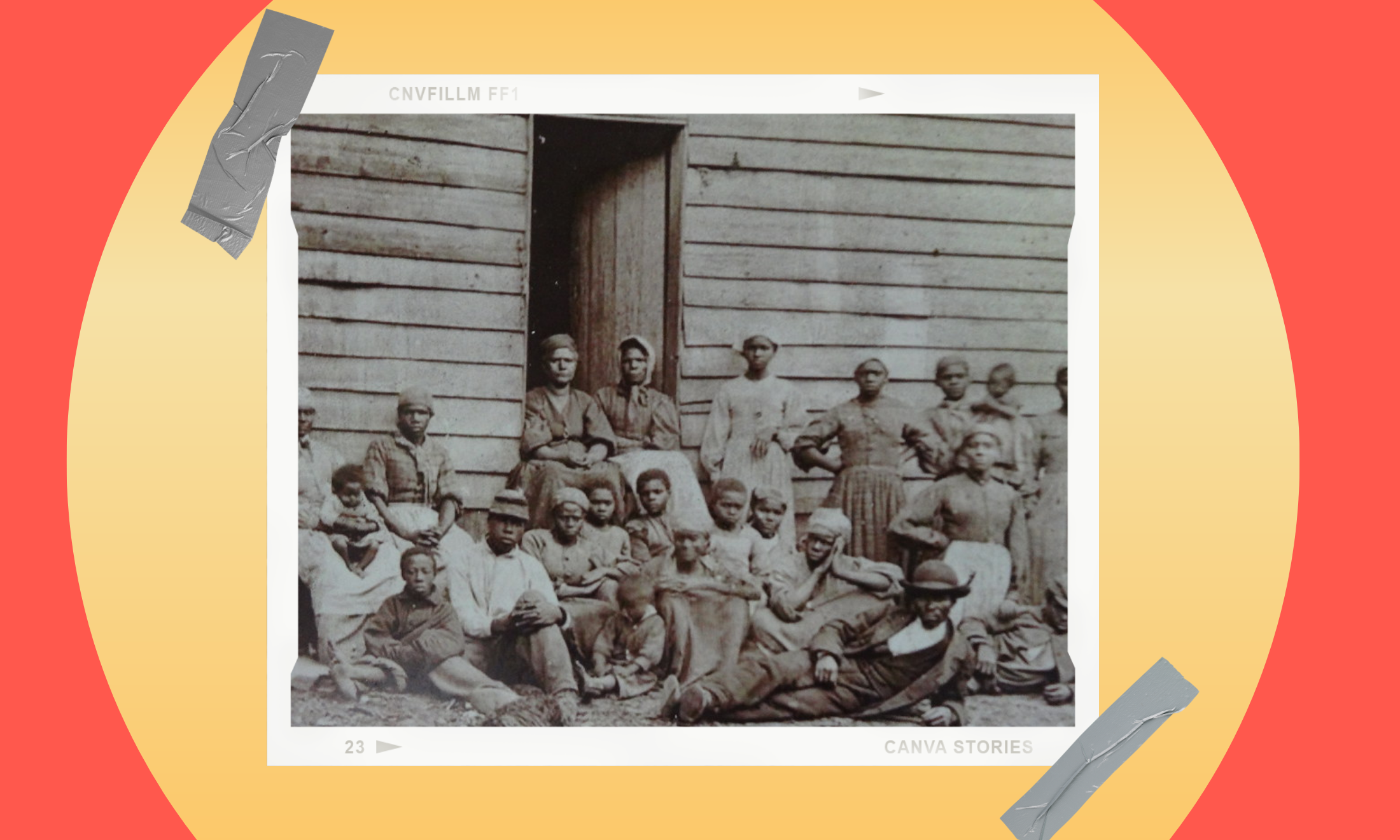

We’re taught that the end of the Atlantic Slave Trade brought about the end of slavery, but slavery is still alive and well in the UK

Notwithstanding its centuries-long relationship promoting and reaping the spoils of slavery, the UK government is now a significant figure leading the global charge against human trafficking, starting with the implementation of the 2015 Modern Slavery Act. This act – which encompasses trafficking, slavery, servitude, and forced sexual and physical labour – is one of the first of its kind in the world. It not only criminalises all forms of slavery in the UK, but it also places a legal obligation on people, especially employers, to aid in the prevention of slavery and sets out extensive guidelines for the identification and protection of potential victims. This is a significant step in the right direction, but it’s not enough. While the UK government’s efforts to end ‘modern slavery’ are commendable, they aren’t having the desired effect. The National Crime Agency stated this year that, despite recent efforts, “it is highly likely that the actual scale of modern slavery […] has increased year-on-year” and that this trend is “likely to continue.”

With Brexit on the horizon, many EU migrants are facing uncertainty about their right to remain in the UK, coupled with a rise in Brexit-related xenophobic hate crimes. Particularly since the advent of Operation Nexus which reportedly targets rough-sleeping Eastern European migrants for deportation, exploited migrant workers are firmly dissuaded from accessing public services due to fears that they will be removed from the UK.

Another uncertainty is the overall effect that Brexit will have on human trafficking from a policy perspective. Andrea Simon, formerly of ECPAT UK, echoed this sentiment, noting that leaving the EU will result in a “lack of access to important European mechanisms such as the European arrest warrant and joint investigation teams, which are vital in investigating cross border crimes.” Furthermore, when legal routes into a country are restricted, individuals are often forced to seek alternative arrangements, leaving them vulnerable to traffickers who may take advantage of the situation.

The unfortunate side effect of inaccessible research and data is that vulnerable demographics – subject to a rapidly changing policy landscape – are unable to educate themselves about a crime that predominantly affects their own communities. It’s important that information about trafficking is made freely available to those who need it, as well as to provide a cohesive evidence base which can be used to sustain pressure on those in government or elsewhere who have the power to solve the problem. It’s time for academic publications to release their grasp on what could be life-saving research and make it accessible to the public. This way, perhaps the affected communities can learn for themselves what human trafficking is and how to spot it, and begin to inform and galvanise government efforts to end to modern slavery.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?