After days of trekking across jungles and mountains to escape violence in Rakhine, Myanmar, almost 300,000 Rohingya Muslims have poured into the muddy fields of neighbouring Bangladesh. Among them: women who gave birth on the journey, the elderly carried by children, and drowned bodies washing up along the border river. Journalists and aid workers on the ground are witnessing an unprecedented human exodus, and warn that more are still likely to come.

The refugees are telling stories of witnessing horrific abuses such as children being beheaded and people burnt alive by the Myanmar security forces and Rakhine Buddhist vigilantes. The latest violent campaign against Myanmar’s Muslim minority began after Rohingya insurgents led coordinated attacks that killed 12 police on 25 August, 2017.

Myanmar authorities said that of the 400 people killed during their latest crackdown, almost all were Rohingya insurgents. However, the UN suspects the death toll is more than 1,000 and there are reports that entire villages have been massacred. Myanmar denies targeting civilians and instead points the finger at the Rohingya militants who they claimed were burning their own homes and killing non-Muslims.

“There are no more villages left, none at all,” Rashed Ahmed, a Rohingya farmer who had walked for four days, told The New York Times near the border. “There are no more people left, either,” he added. “It is all gone.”

Even though the retaliatory violence against the Muslim minority began two weeks ago, journalists, and by extension the world, have witnessed new fires being lit in abandoned villages in western Myanmar, extinguishing any hope of Rohingyas returning to their homes.

The recent bloodshed in Myanmar’s Rakhine state is not the first time Rohingya Muslims have fled into Bangladesh. As the world’s most persecuted community according to the UN, they have been seeking refuge in present-day Bangladesh since the 1700s.

The South Asian nation is already host to more than 400,000 Rohingya who fled persecution in the 1970s and early 1990s. Communal violence between Rakhine Buddhists and Muslim Rohingyas broke out again in 2012 and since then, a number of refugees have crossed porous land borders and braved rocky waters in rickety boats, hoping for safety in Bangladesh, Thailand and beyond.

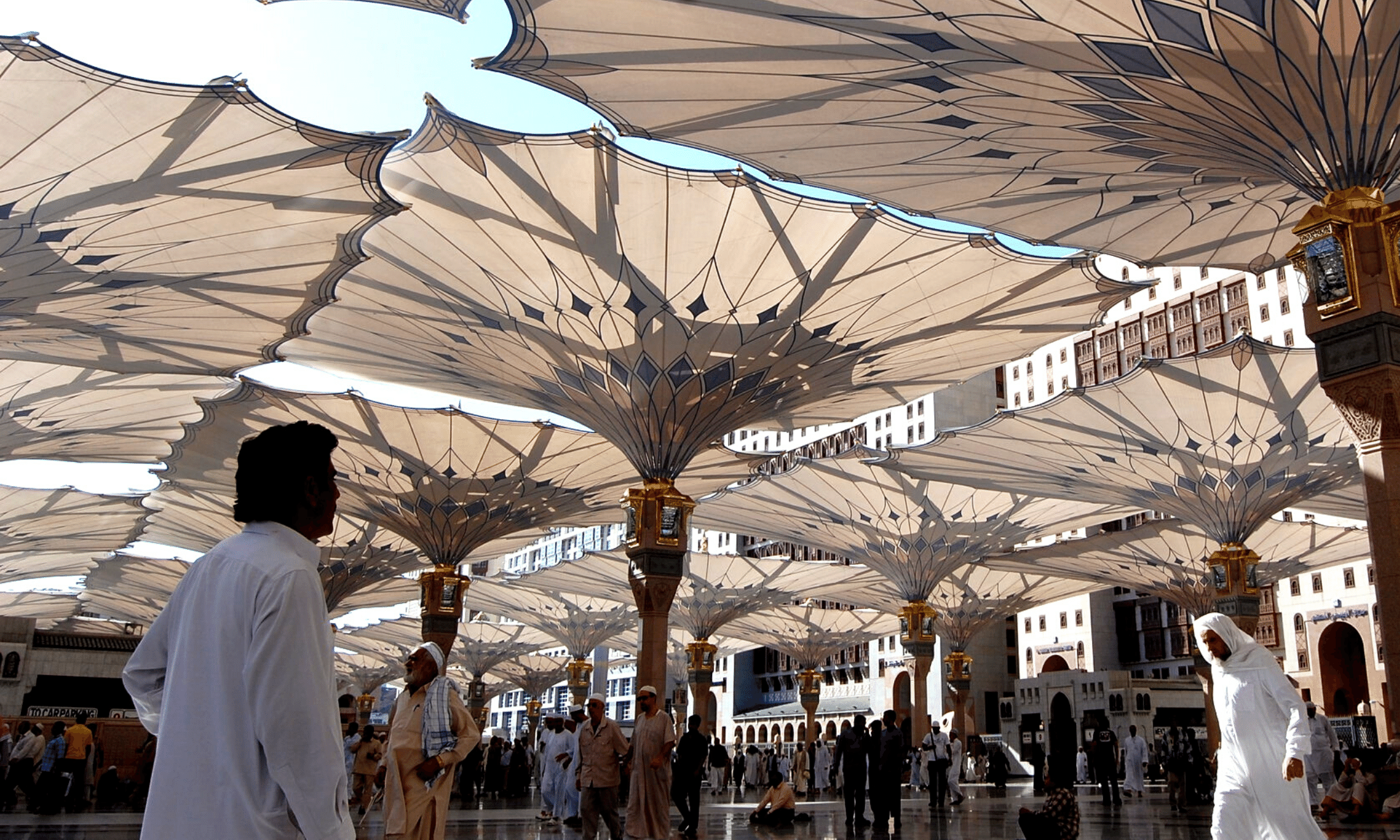

Analysts blame the 2012 riots and the Myanmar government for the conditions that led to a small insurgent group being formed in Saudi Arabia last year by young Rohingya exiles. Though the group, now calling itself the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA), is believed to have received militant training from Pakistan and Afghanistan, and funding from the Middle East, there is no evidence to suggest they suggest support a transnational jihadi agenda.

ARSA describe themselves as “the guardians and protectors of the oppressed Rohingya,” and claim they are waging “a defensive war with the brutal Burmese military regime.” After recruiting and training local Rohingya men, they launched their first attack on security forces in Myanmar last October. Amnesty International documented the Myanmar security forces’ retaliation to that attack – killings, torture, rape and burning homes – and warn their actions may have amounted to crimes against humanity.

Myanmar, an overwhelmingly Buddhist country, does not want its 1.1 million Rohingya population. Considered to be illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, the Rohingya are denied citizenship and rights in Myanmar, despite claiming centuries-old roots in Rakhine.

Bangladesh, however, has an equally long history of rejecting the Rohingya and initially pursued a policy of pushing back thousands of refugees into violence-wrought Rakhine. It now struggles to make space and provisions for the latest influx of refugees, and the civilian government of Myanmar’s de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi faces mounting global criticism for refusing to acknowledge the magnitude of the military-led operations against the Rohingya minority.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has accused Myanmar of “genocide”, a word many others seem wary to use just yet. The United Nations secretary general Antonio Guterres said the army’s attempts to root out “terrorists” risked becoming ethnic cleansing.

Nobel peace prize winner Suu Kyi, once hailed as her country’s Nelson Mandela, however, has a different perspective on the issue. In April, the democracy activist, once held under military house arrest for 15 years, told the BBC, “It is a matter of people on different sides of the divide,” and that she thought “ethnic cleansing is too strong an expression to use for what is happening.”

But with the current wave of violence marking the worst documented so far, and with rights groups saying the testimonies alleging rape, murder and arson point to a final crackdown to rid Myanmar of the Rohingya, what else can we call it?

Unsurprisingly perhaps, a change.org petition to revoke Aung San Suu Kyi’s Nobel peace prize has surpassed 400,000 signatures and fellow nobel prize winners are appealing Suu Kyi to intervene on behalf of the Muslim minority. Malala Yousafzai, the youngest-ever peace prize winner, said her “heart breaks” every time she sees the news and that “the world is waiting” for Suu Kyi to act. In an open letter, Nobel laureate Desmond Tutu called on his “dearly beloved sister” to end the “unfolding horror” and “ethnic cleansing.”

But even with her international reputation rapidly disintegrating, Aung San Suu Kyi’s refusal to speak out or take meaningful steps to prevent the further persecution of Rohingyas isn’t a shock. The Buddhist majority she represents hate the Rohingya and would gladly see them gone. Not only that, but Suu Kyi does not control the military, the same one that kept her under years of house arrest, nor do they trust her.

However, that is not to say that her inability to stand up and represent the downtrodden as she once did before is not deeply disappointing. It’s deadly. And echoing what the anti-apartheid leader Archbishop Tutu said in his letter, if the political price for her position of power is her silence, “the price is surely too steep.”

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?